Perhaps it would be better if Myanmar’s civil war became a ‘forgotten conflict’

A belated outside push for a negotiated settlement would reward the military junta.

It’s become fashionable in some quarters to suggest the three-year-old Myanmar civil war might be solvable if only more people remembered that it was taking place.

Julie Bishop, a former Australian foreign minister appointed the UN Special Envoy on Myanmar in April, recently gave her first address to a UN General Assembly committee, in which she warned that “the Myanmar conflict risks becoming a forgotten crisis.”

One might enquire by whom this conflict is apparently becoming “forgotten.”

One can hardly say with a straight face that it has been forgotten by the 54 million people of Myanmar, nor by the 3.1 million people who have been displaced, nor the million or so Rohingya who must still live in hell-hole refugee camps abroad because they know the military junta wants to finish the genocide it started years ago.

It is certainly not forgotten by the people who matter the most.

But the claim also invites the question: Would there be any improvement if the conflict was less forgotten?

Frankly, if any Western democracy or the UN wanted to intervene, they’ve had several years to do so.

If ASEAN wanted to stop play-acting at mediation, it’s had since April 2021 to carve some teeth into the Five-Point Consensus, its unrealized peace plan.

Post-colonial settlement

This conflict has been raging since February 2021, though some might say, quite accurately, that it has actually been waiting to erupt since the 1950s.

Whereas nearly every other Southeast Asian country underwent something like a civil war or democratic revolution after gaining independence from European colonial powers, Myanmar never did so. That process was left stillborne by the military coup of 1962.

Because the military has shown that it cannot be trusted to share power with a civilian government, only now, do the people of Myanmar have the possibility of throwing off the foul despotism that has enchained them throughout the post-colonial era.

RELATED STORIES

Myanmar junta chief says ready to talk to rebel groups

Myanmar junta chief seeks China’s help on border stability

Junta airstrikes kill 540 Myanmar civilians since new year, mostly in Rakhine state

Only now can they decide whether they want a full-blown military regime of the kind they’ve had for decades, a semi-democracy in which the military retains political power and the ability to launch a putsch if threatened – as they had between 2016 and 2021 – or something that aspires to genuine democracy.

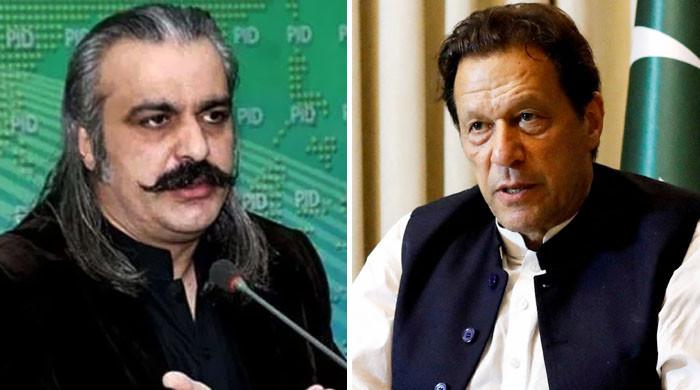

Bishop, who revealed has met with the junta leader Min Aung Hlaing, said “Myanmar actors must move beyond the current zero-sum mentality.” She also spoke of “an agreed solution” and “reconciliation.”

However, it shouldn’t need to be pointed out that civil conflicts are almost always zero-sum.

Vietnam didn’t remain partitioned after 1975. Laos didn’t get a communist-royalist coalition the same year. Malaysia expelled Chinese-majority Singapore out of the federation in 1965. The Marcos and Suharto dictatorships eventually fell.

When the international community finally remembered that the East Timorese were being massacred by Indonesian colonists, after decades of intentional forgetfulness, the conflict didn’t end with Timor-Leste being half-independent and half an Indonesian province.

“Peace and reconciliation” is a fine principle, too noble to be besmirched by association with the murderous junta in Myanmar.

In any case, the time for reconciliation is after a conflict.

Legitimizing the coup

Any return to the status quo ante in Myanmar — the only outcome if an “agreed solution” was possible — would hardly be a moral solution, let alone a stable one.

For starters, it would legitimize the 2021 coup.

Min Aung Hlaing and the generals who have murdered, tortured, and brutalized the Burmese people would presumably retake their seats in the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw, instead of in the International Criminal Court.

If the Tatmadaw were allowed to return to their barracks and keep their political power, all that would be achieved would be to delay another coup for a few more years.

Such a solution would also involve the opposition ethnic armies and militias handing back authority of the areas they control — the majority of the country — to a coalition government that will never be able to command the loyalty of most people.

This doesn’t sound like a recipe for stability or peace.

Yet it wouldn’t be surprising if Min Aung Hlaing is now whispering talk of reconciliation in the ears of foreign visitors. His forces are losing, and his life is threatened by outright defeat or a palace coup.

Premature settlement

One wonders how much of what Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi told Bishop during their meeting in August informed her thoughts about reconciliation.

Beijing now reckons that a junta-conducted election is the only off-ramp that favors China’s interests and the only way the military can maintain its political influence in a post-conflict government.

As Zachary Abuza wrote a few weeks ago: “Beijing believes that a corrupt and pliable Myanmar government that includes the military will best serve Chinese interests…Giving the junta a seat at the table gives them yet another opportunity to kick the forces of democracy and federalism in the teeth.”

This kind of accommodation could flow from what Bishop appears to be advocating, even as she says “the people of Myanmar, having suffered so much, deserve better.”

But shouldn’t the matter of what better is be decided by those very people – and not to an international community that wanted nothing to do with their struggle in 2021 but is now happy to sit down with Min Aung Hlaing and talk about reconciliation?

If having your revolution thrown under the bus and being instructed to make peace with your tyrants is the price to pay for more international attention, perhaps the Myanmar opposition might prefer that their struggle becomes “forgotten.”

David Hutt is a research fellow at the Central European Institute of Asian Studies (CEIAS) and the Southeast Asia Columnist at the Diplomat. He writes the Watching Europe In Southeast Asia newsletter. The views expressed here are his own and do not reflect the position of RFA.

![EISH WENA: SA mom dances with joy as daughter wins award [Video]](https://www.thesouthafrican.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Mmaa.jpg.optimal.jpg?#)